Snake skin and saving memory. Barbara Kowalewska writes about ‘White Snake’

Among all animated films presented at the Festival, one of the most interesting ones is the Chinese ‘White Snake’ addressed to young viewers. For Europeans, the production will be attractive and challenging at the same time, since it’s based on many Far Eastern spiritual symbols and thus not easily interpretable. However, I see this film as a great adventure – you don’t have to know everything you see in it or overthink too much, you just have to open up to the symbols of another culture and let the associations flow. It may be a more accurate attitude when watching this image.

The World of Collective Imagination

The plot is inspired by The Legend of the White Snake (there are many versions of it) and takes place in a mythical land where the evil General uses the energy of demon snakes in search of immortality. Xuan, a young boy from the Snake Catcher Village, and Blanka, a snake-woman, are the main characters in the story. People are afraid of snakes, and demons, in turn, claim that people are traitors and thieves. There are complicated relationships binding Xuan and Blanka together, since she turns into a half-human, half-snake in moments of strong emotions. The film is filled not only with Chinese, but Japanese mythological motifs in which a snake is often identified with negative emotions felt by women, mainly those seeking revenge. However, Blanka is a white snake, and, in Japanese legends, white snakes are a symbol of prosperity and luck. This bipolar symbolism is the driving force behind the story. Xuan, a gentle character full of compassion, tries to defeat the demonic side of Blanka’s nature by asking about the origins of her demonic anger, and warming up her freezing, half-snake body with his own heat. Of course, he does this because he’s fallen in love with her. As the action develops, other elements of the Far East culture appear: Book of Changes, the Eight Gates of Seoul and the yin and yang symbolizing to opposing but complementary forces.

Jade, Origami and Maple Trees

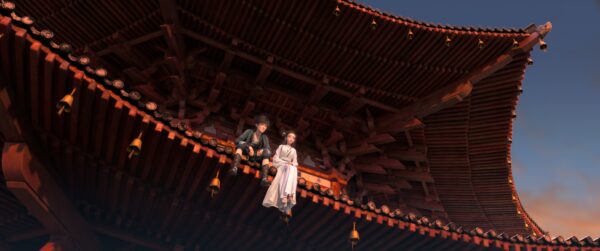

The animation can appeal to young people through both its storytelling and visual content. The characters are neatly drawn and the background is rich in colour and elements characteristic of Asia: hills lined with red maple trees, cherry blossom flowers dancing in the wind, magical powers embodied in sky lanterns, and the General’s armed forces in paper, origami airplanes. Various computer techniques were used to animate the battle scenes. An interesting part of the story is Xuan’s stay in the Precious Jade Workshop, where an opium-smoking woman turns him – at his request – into a demon, but takes away part of his life energy (nothing comes for free). This is a clear reference to the important Buddhist belief of reincarnation and transmigration of human soul into other life forms. The Precious Jade Workshop is a place of miracles, and the ingenuity and humour of the animation’s authors peak here. It’s worth seeing a film, even if only for this scene.

Memory and Enlightenment

The film is also a story about the memory loss and recovery, the price of which is drifting away from the Buddhist enlightenment, because “a moment of joy costs 500 years”. Blanka, who in the end fails to save Xuan from his mortality, does not want to forget about him and is determined to find him and his soul that survived in the world. Although her sister reminds her that in the process of reincarnation Xuan could’ve already become someone or something else, Blanka keeps missing him, and sees her longing as more important than the desire to reach enlightenment. Without spoiling the ending, I can risk saying that this story is a contemporary revisit of traditional, spiritual symbols and a tribute to memory that makes us human. Here, saving a soul is done differently than in the old books.