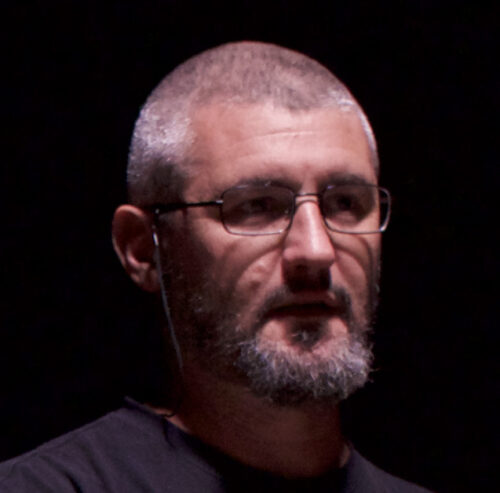

The name can tell a lot about us. Gaspar Scheuer, the director of ‘Delfín’, as interviewed by Kuba Armata

Delfín’s biggest dream is to join a children’s orchestra rehearsing in a neighbouring village. The trip and the experience will not only affect him, but also his father.

Kuba Armata: Who makes a more demanding audience: a child or an adult?

Gaspar Scheuer: That’s a good question to which I don’t think I have a straightforward answer. A child becomes absolutely engrossed in the story they are watching. It’s a precious quality, bringing them closer to an ideal viewer. The child leaves all duties and plans behind and completely immerses in the setting. I found it a huge challenge to make a film which is not children’s cinema per se but will be attractive for viewers of any age. The possibility of decoding the story on several levels is something very typical of the cinema. Some films which exerted a strong influence on us in the past, when re-watched in adult life, may send a completely different message. It is a very important criterion to me. Personally, I have four or five films I tend to come back to every now and again and I always get the impression that I interpret them anew each time.

Are there many films addressed to young audience made in Argentina, where you’re from?

Unfortunately not, it is a neglected audience in that respect. A few days ago, my kids and I were watching a film addressed to young viewers. After 20 minutes, we turned it off in silence. A while later, Simon, my 9-year-old son, came up to me and asked: ‘Do the people who make films for kids think we are stupid?’ Young audience of today immediately sense when someone underestimates them as viewers. I guess this is exactly why Disney cinema has stayed strong. We may find the moral standards or the value system presented there debatable but no disregard for the child could be imputed to its creators, since children thrive on imagination, fantasy and mystery. Disney films offer that to young audience in abundance. The question is, therefore: how to make a film which, despite the financial constraints, will still be entertaining without compromising on artistic values, original style, describing the world around us? I wanted ‘Delfín’ to be exactly that kind of attempt.

How did you get the idea for the story presented in ‘Delfín’?

‘Delfín’ is my third full-length film. Each of my previous productions took about five years to make. One night, I felt I needed something more light-hearted, with a shorter production schedule. I wanted to make a film which I could watch at the cinema with my children. That did not mean, as I have mentioned before, a production strictly for kids, but one which a young viewer would find easy to follow. As a result, in place of the previous darkness and shadow – along came a sudden streak of light. Bigger sets and slow pace were replaced with a clearer rhythm and more intense plot line. Adagio turned into andante.

Music plays a very important part in your film. Do you, like your protagonist, associate it primarily with freedom?

With transcendentalism, freedom, the possibility to make and create new worlds. In all my films, even the short ones, there is always someone who sings or plays an instrument. The music in ‘Delfín’ plays a very important role in the plot line. The young protagonist learns how to play the French horn but as he doesn’t have his own instrument – he practices using an ‘instrument’ made of plastic, a garden hose and a funnel. The funny thing was that once I had imagined this construction, I watched a YouTube video where Martin Lawrence, a renowned British horn player, demonstrates how to make exactly the same instrument and later uses it to play Bach.

Your film tells the story of a complicated relation between an 11-year-old boy and his father. Traditional roles have been reversed here. It is Delfín who is much more responsible than the adult man and it is he who actually looks after his father.

That was exactly what I had in mind when I started to work on the screenplay. In a relation with a child it is usually the adult who needs to learn. Parenthood requires providing answers we are never prepared to give beforehand. We often improvise. Children, in turn, respond and behave in a more natural way – therefore often staying closer to the truth. Hence, an adult needs to be alert, have their eyes open at all times so as not to lose sight of the thing a child can learn.

Do you perceive your film as a kind of tale?

I see it as a story combining the contemporary, social aspects with tradition and myth. We can imagine that what Delfín plays is one of the first instruments discovered by the prehistoric people gathered round by the fire. After the feast, one of them started to examine the bones of the animal they’d just eaten and discovered that by blowing the horn in a certain way, various sounds may come out conveying joy or melancholy. In life, there are unexpected encounters with mysterious people who can teach us something we would never suspect them of. Even a person’s name can tell us something about their destiny. In parallel with these interpretations, the film touches upon the everyday, concrete reality of Latin America, child labour, difficult living conditions and extreme poverty.

You mentioned the role of the name. In one of the scenes, when an older man learns that the boy’s name was chosen by his mother, he says that one’s name indicates destiny.

That is an old Latin phrase – nomen omen – which I like very much. I think that in this infinite tapestry, which is the universe, there is little we can really understand and anything can serve as a key to deciphering something, to grasp meaning. How, then, could a word that will accompany a being for life be meaningless? It will be their ID tag, sometimes the first or only thing we will know about them. What I cannot answer is whether destiny exists. If it does, it is certain that a name can tell us something about it.

How did you come across Valentino Catania, who plays the lead role?

When we decided to organise the casting in Los Toldos, I had doubts as to whether we would be able to find a child there who could stand up to playing such a complex character. Los Toldos is where I lived until I was 18 and I often go back there. Interestingly, it’s also the home town of Eva Perón. About 50 children took part in the casting, which is a pretty decent result for a small town. Valentino is the son of a long-time friend of mine whom I have known since birth. I would never have thought he would be interested in playing in a film. In fact, I believe that until that moment Valentino himself could not have imagined it either. Undeniably, his audition was really beautiful. Let’s not forget that boys that age change a lot in a short time. At the time of the casting, he was a year younger than the protagonist in the film but he understood and interpreted everything with incredible sensitivity. I had no doubt that he could play Delfín. Shooting the film wasn’t easy because it was quite challenging to combine the world of a child with the reality of working on set. However, even in the most difficult moments, we knew that what was happening in front of the camera was authentic and had an intensity that can rarely be captured.